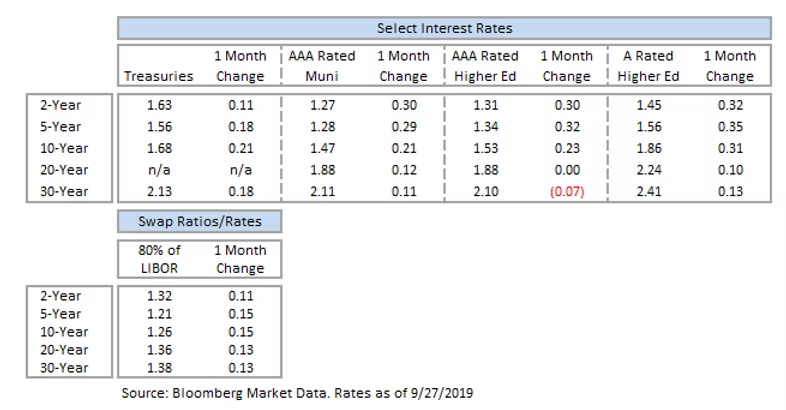

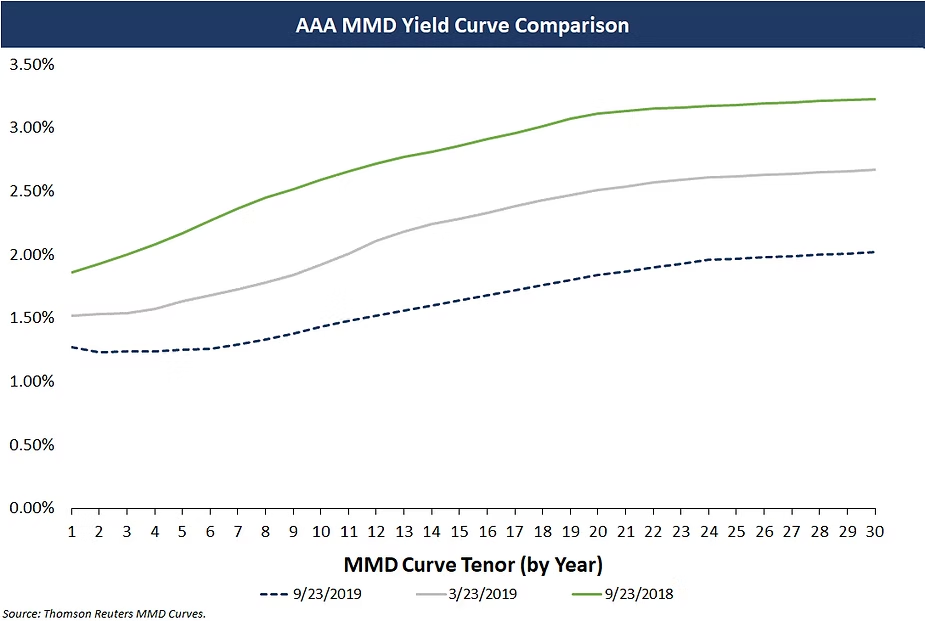

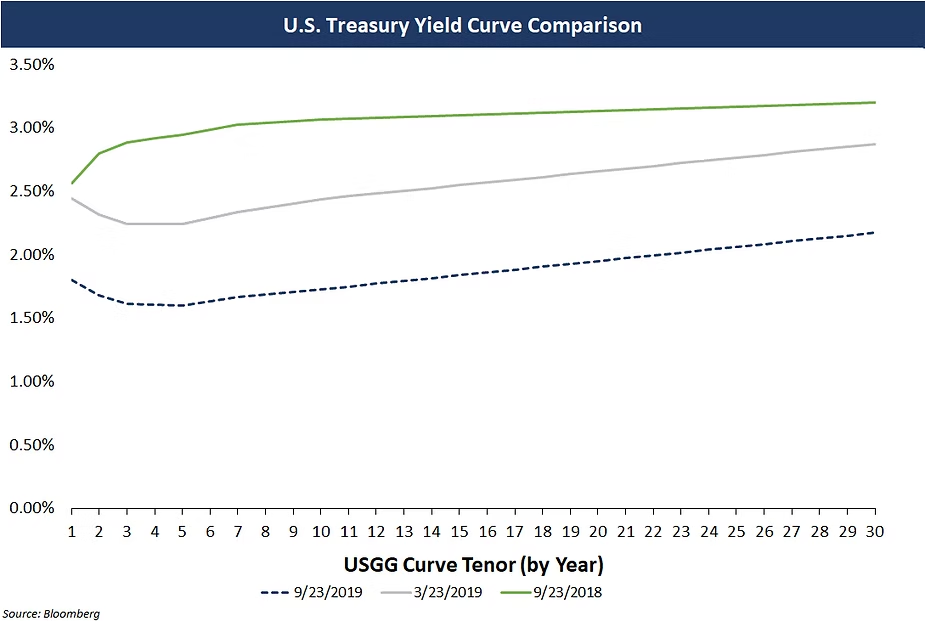

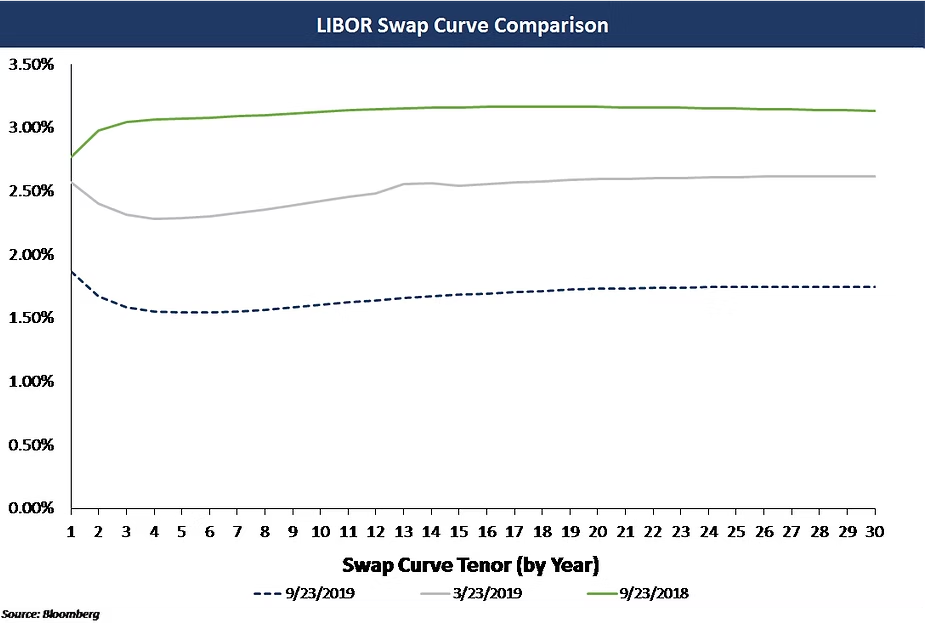

Rates have fallen and yield curves have flattened (and in some areas inverted) significantly since the start of the year.

By virtue of these lower rates, many borrowers have realized positive impacts to their capital structure in a variety of different ways: embarking on a new financing, a new synthetic fixed rate structure, or simply feeling the effects on an existing “naked” variable rate position. However, many borrowers are also currently experiencing an increase in the negative MTM (mark-to-market) values of their swap portfolios.

A common swap position held by those locking in a synthetic fixed rate structure is that of the fixed rate payer. When variable rates fall, these positions move out of the money as the fixed rate paid drifts higher than the floating rate received. In this structure with rates falling, looking at a swap value in a silo can appear negative; however, when taken in concert with the underlying debt position, this movement should be viewed as part of an overarching hedging strategy. By locking in a synthetic fixed swap rate, a borrower gives up the opportunity to benefit from potential downward movements in its variable rate debt formula but receives a guarantee that their interest expense won’t move above its effective fixed rate (swap rate plus the underlying credit spread) if interest rates rise. The objective behind a perfectly synthetically fixed structure is to lock in a cost of capital, no matter the level of rates. In theory then, as rates have fallen in the past months, the net borrowing rate of existing synthetically fixed structures has remained constant.

A potential externality of this hedge objective is a negative swap value. As the capital markets cope with an inverted yield curve and flattened forward rates, the resulting effect on swap values can be a source of stress for treasury directors and controllers alike. It’s never easy to see increases in liabilities – especially derivative liabilities – and have to explain these changes to senior leaders, finance committees and broader financial statement users. The two key considerations to keep in mind when viewing a negative swap MTM value are related to 1) accounting treatment and 2) potential collateral posting. These two considerations can vary depending on the entity and hedging structure, but below is a crash course on how these two items can be approached.

Accounting Considerations

Collateral

The Shield Conclusion

[1] An ISDA agreement is needed to consummate the derivative transaction between the user and counterparty bank.

About the Authors:

Craig Haymaker, Chief Operating Officer

Craig oversees the risk management consulting, hedge accounting and valuation groups at HedgeStar. He is a subject matter expert in financial reporting and accounting for debt, equities, derivatives and other financial instruments. Craig holds a Bachelor of Business Administration degree in Accounting from Stonehill College, and earned his CPA accreditation in 2010.

Comparable Issues Commentary

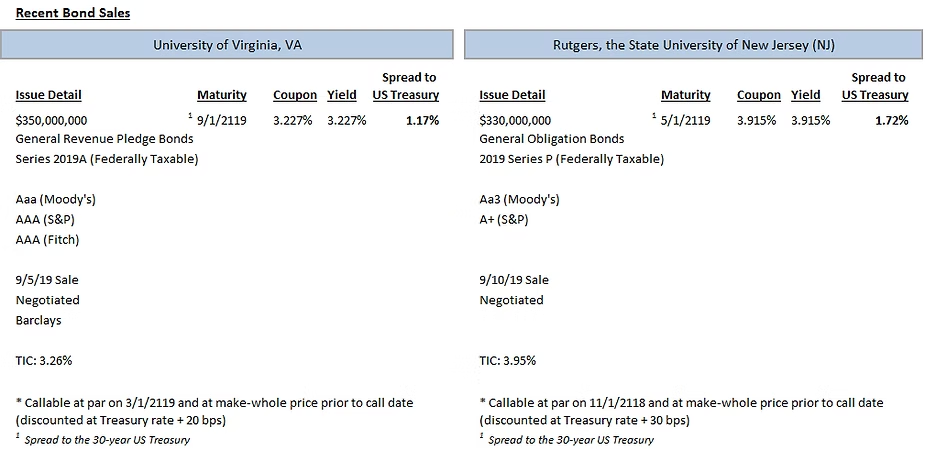

Shown below are the results of two negotiated, taxable higher education century bonds that sold in the month of September. The University of Virginia (“Virginia” or “UVA”) and Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey (“Rutgers”), priced their bond issues on September 5th and September 10th, respectively. Both deals were sized similarly, with Virginia borrowing $350 million and Rutgers borrowing $330 million. Virginia’s deal carried “AAA” ratings from all 3 major rating agencies, while Rutgers’ bond issue carried ratings of “Aa3” from Moody’s and “A+” from S&P.

The two transactions each were primarily intended to finance future capital improvements on the Universities’ campuses, with Virginia also utilizing the issue to refinance outstanding commercial paper obligations and to reimburse itself for previously expended capital project costs. Both deals were structured with 100-year bullet maturities, using the “century bond” structure that has garnered renewed interest from higher education institutions due to the dramatic decline in long-term borrowing rates in 2019. Both UVA and Rutgers were able to lock in sub-4% borrowing rates – along with the University of Pennsylvania (“UPenn”), which issued its own century bond in August, these 3 transactions are the first of their kind in U.S. higher education to achieve 100-year borrowing costs below that 4% threshold. On a spread basis, Virginia’s century bond priced 117 bps above the 30-year treasury (comparable to UPenn’s 115 bp spread in early August and 20 bps tighter than UVA’s prior 2017 century bond issue), while lower-rated Rutgers priced 172 bps above the 30-year treasury the following week.