The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 has created significant new challenges for all higher education institutions and further exacerbated existing challenges. Faced with unprecedented disruptions to “status quo” methods of operation last March, colleges and universities have adapted admirably on the fly, shifting students to remote or hybrid learning solutions while managing expenses to compensate for revenue losses from various sources, including housing and auxiliaries, athletics, and overall headcount. Prior to the new challenges posed by the pandemic, the U.S. higher education sector already faced considerable headwinds, with “negative” outlooks from all three major rating agencies since 2019 (note: Moody’s revised its outlook to “stable” very briefly in 2020 before moving back to “negative” after the onset of COVID-19). Given some positive momentum to start off 2021, including extraordinary government stimulus funding for colleges and universities authorized by the American Rescue Act passed in March and acceleration of vaccine deployment across the U.S., is there a light at the end of the tunnel for higher education? Opinions vary among the rating agencies, but all agree that major challenges remain for the sector in 2021 and beyond.

Moody’s – Outlook Revised to Stable, but Headwinds Remain

Notably, after beginning 2021 with the sector on “negative” outlook, Moody’s recently changed their outlook on the higher education sector to “stable”, citing improved prospects for revenue growth over the next 12-18 months.[1] One key driver for this change is the growing likelihood of students returning in full to campuses in fall 2021, which would allow for a near-normal resumption of “standard” operations. Improving tuition and auxiliary revenues for institutions in fiscal 2022, despite expectations for significant revenue declines of 5% – 10% in fiscal 2021, are other positive drivers. Additionally, the passage of the American Rescue Plan stimulus package in Congress, providing additional direct aid funding to higher education, was a major influence, serving both to offset pandemic-induced revenue losses and expense increases as well as to meaningfully bolster state economies and thereby reduce the risk of funding cuts to public universities. Finally, Moody’s also pointed to economic growth and the continued strength of the financial markets as additional positives for universities, with these factors serving to encourage growth of endowments as well as sustaining philanthropy and improving the ability of families to pay for tuition. Offsetting risk factors include longer-term demographic challenges as well as potential setbacks in the COVID-19 recovery, which could result in further disruptions to universities heading into the fall 2021 semester, and potential economic disruptions, which could threaten state funding, endowment balances, and the market position of institutions in the event of a recession or economic downturn.

On the debt management front, Moody’s also has published its thoughts on the assortment of strategies currently being utilized by colleges and universities to adjust and position their debt and liquidity profiles in the face of the pandemic.[2] Institutions have taken a variety of approaches to address debt and liquidity during the pandemic, with a number of schools utilizing “scoop and toss” refinancings to create short-term budget relief, some opting to convert variable or synthetic fixed-rate debt into pure fixed-rate structures, and still others taking out (sometimes sizable) lines of credit or taxable long-term financings to bolster liquidity and/or lock in low-cost long-term capital in a favorable interest rate environment. In general, Moody’s has taken an accommodative view of these strategies, viewing them as “tools in the toolbox” for higher education institutions to manage their operations and liquidity needs in a relatively low-cost manner. Nevertheless, Moody’s highlights strong governance as critical when taking such actions, particularly for relatively weaker credits in the lower “A” and “Baa” categories carrying less financial flexibility than higher-rated institutions. If universities increase overall long-term fixed costs through debt service deferral or meaningful new borrowing without a plan to address the challenges driving those decisions over time, these decisions could present a significant credit negative for institutions down the road.

S&P and Fitch – Outlooks Remain Negative as Pandemic-Related Challenges Expected to Persist

Unlike Moody’s, both S&P and Fitch have maintained their “negative” outlooks on the sector uninterrupted since 2018 and 2019, respectively. Both rating agencies reaffirmed this outlook heading into 2021,[3] and have not revised their positions to date. In particular, while S&P highlighted the recent American Rescue Act stimulus as a positive source of fiscal relief, they maintained their view that the sector’s challenges are unlikely to be offset by stimulus alone, with a financial recovery taking time and varying widely by institution.[4] Supporting these views, S&P had 39% of its rated colleges and universities on “negative” outlook as of January 2021 (Fitch had a smaller, though still significant, 14% of rated colleges/universities on “negative” outlook as of December 2020, for reference). S&P was also the only rating agency to shift many of its rating outlooks for higher education institutions to negative en masse last year (in April). While some of those outlooks may have been shifted back to “stable” since January, S&P remains the most bearish rating agency on higher education by this particular measure.

In what is a common view across the rating agencies, both S&P and Fitch highlight the ability of stronger institutions (such as flagship universities and schools with higher selectivity, reputation, and/or market position) to be able to weather the challenges of the current market environment far better than lower rated institutions in the “BBB” categories and below, with a gap in credit quality between lower and higher-rated schools that will continue to widen. Each also have been more hesitant than Moody’s to date to predict a full or near-full return to normalcy in fall 2021, with persisting expectations of fewer students on campus and lower tuition and auxiliary revenues lingering into fiscal 2022. S&P in particular also highlighted regional differences as a key factor, anticipating a very uneven rebound across the U.S. depending on the speed and magnitude of regional economic and health recoveries from the impact of the pandemic. Privatized student housing was another particular risk that S&P found to be quite severe, with extraordinary pressures on these projects driving the entirety of its rated privatized housing portfolio to “negative” outlooks, and 35% of the projects also receiving rating downgrades in 2020. Overall, while both S&P and Fitch see potential for some easing of the pressures facing higher education institutions in 2021, they are less optimistic than Moody’s about these positive trends outweighing the pronounced negative challenges that remain all too prevalent for the sector as a whole.

Conclusion

While opinions differ to an extent between the rating agencies on the relative credit stability of the higher education sector, each agency clearly acknowledges the significant challenges that remain for colleges and universities in 2021 and beyond. Despite increasingly positive indications of a partial or full recovery to semi-normalcy in fall 2021, with widespread vaccinations and recent stimulus buoying the prospects of higher education going forward, the broader demographic trends and operational challenges facing institutions remain very much present. Accordingly, the credit climate is still a difficult one for higher education institutions, with few rating upgrades coming from any of the rating agencies and meaningful downgrade risk still present, particularly for lower-rated schools. If your college or university has an upcoming rating review or is considering applying for a new credit rating, we encourage you to contact a Blue Rose advisor to plan how to articulate your institution’s credit strengths and respond to questions and concerns the rating agencies may have in the current market environment.

[1] For additional information on Moody’s outlook for the higher education sector, see the following two research pieces: “Higher Education – US: 2021 Outlook Negative as Pandemic Weakens Key Revenue Streams,” published December 8, 2020, by Moody’s, and “Higher Education – US: Outlook Revised to Stable as Prospects for Revenue Growth Improve,” published March 22, 2021, by Moody’s.

[2] See “Higher Education – US: Debt Strategies Provide Flexibility Amid Pandemic; Some Carry Longer-Term Risks,” published March 4, 2021, by Moody’s for additional detail on this topic.

[3] For reference, see “Outlook for Global Not-For-Profit Higher Education: Empty Chairs at Empty Tables,” published January 20, 2021, by S&P, and “Fitch Ratings 2021 Outlook: U.S. Public Finance Colleges and Universities,” published December 8, 2020, by Fitch.

[4] See “Across U.S. Public Finance, All Sectors Stand to Benefit from the American Rescue Plan,” published March 18, 2021, by S&P for additional detail on S&P’s views on the impact of the recent stimulus bill.

About the Author:

Maxwell S. Wilkinson | Assistant Vice President

Max Wilkinson joined Blue Rose Capital Advisors in 2016. In his role of Assistant Vice President, he will be tasked with growing client management responsibilities, in particular ensuring that our clients’ transactions run smoothly through closing. He has significant expertise in the preparation of credit and debt capacity analysis and is experienced with the pricing and execution of fixed rate bond transactions, direct purchase bonds, and derivative and reinvestment products. Mr. Wilkinson is closely involved in every step of the financing process for clients, from initial capital planning stages all the way through closing.

Prior to joining Blue Rose, Mr. Wilkinson worked as a Reinsurance Analyst intern at the London office of JLT Re (now Guy Carpenter), where he provided analytical support as part of JLT’s property and casualty brokerage teams. Mr. Wilkinson also worked for years as a member of Yale’s chapter of the global nonprofit organization AIESEC, where he served on the executive board as Vice President of Business Development in 2015.

Mr. Wilkinson holds a bachelor’s in economics from Yale University. He passed the MSRB Series 50 Examination to become a qualified municipal advisor representative. You can reach Mr. Wilkinson at [email protected].

Blue Rose Announcements

Did you miss our webinar on the LIBOR Transition?

Blue Rose partnered with our affiliate company, HedgeStar, to discuss the impending LIBOR transition. What are the latest insights and market reactions? How should borrowers respond, and what are the next steps? These questions and more were answered on this critical and time-sensitive topic.

In this session, we focused on the transition from the London Interbank Offered Rate (“LIBOR”) to the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (“SOFR”) from a borrower’s perspective. We addressed SOFR “math,” with insight into the mechanics of the transition, and answered the question plaguing so many on this subject – what should I do next?

Do you want to learn more? Reach out to a Blue Rose advisor today!

952-746-6050 / i[email protected]

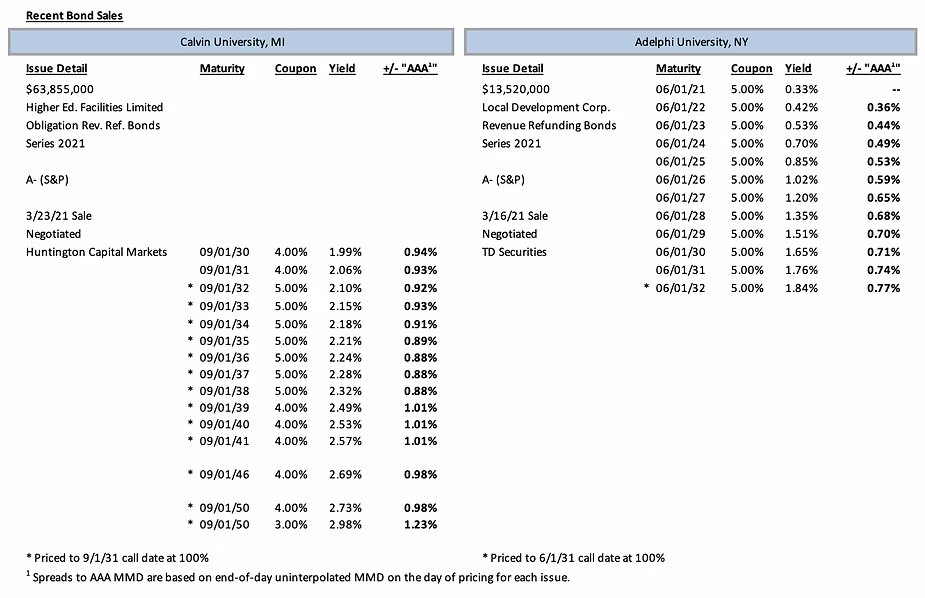

Comparable Issues Commentary

The two universities priced into a relatively strong tax-exempt market, with tax-exempt interest rates stabilizing in March after significant increases at the end of February. Both institutions priced on positive days in the market as well, with MMD completely unchanged for Adelphi’s pricing on March 16th and reduced by 3 bps across the entire yield curve for Calvin’s pricing on the 23rd. Credit spreads for Adelphi ranged from 36 to 77 bps on its noncallable maturities, benefitting from the New York state tax advantage to pricing. Calvin sold its callable 5% coupons at spreads ranging from 88-93 bps, with 4% coupons pricing in the 98-101 bps range and the lone callable 3% term bond in 2050 pricing at a spread of 123 bps above MMD.

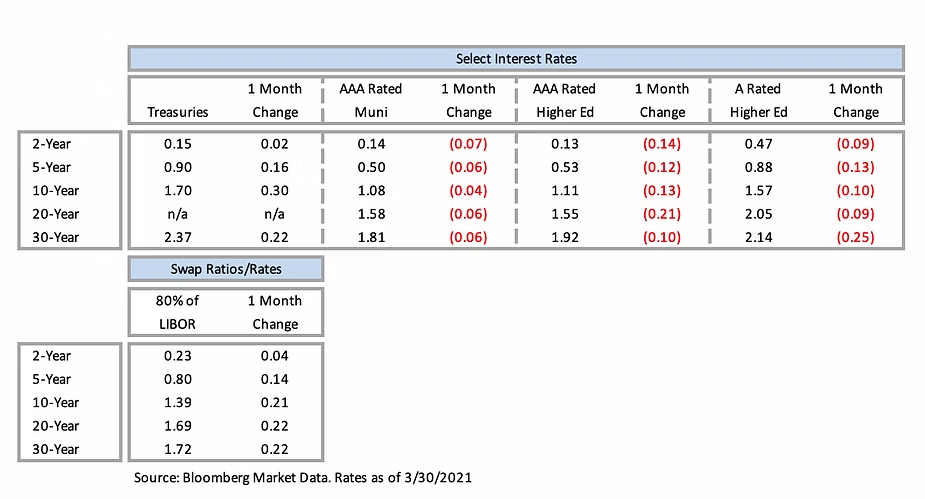

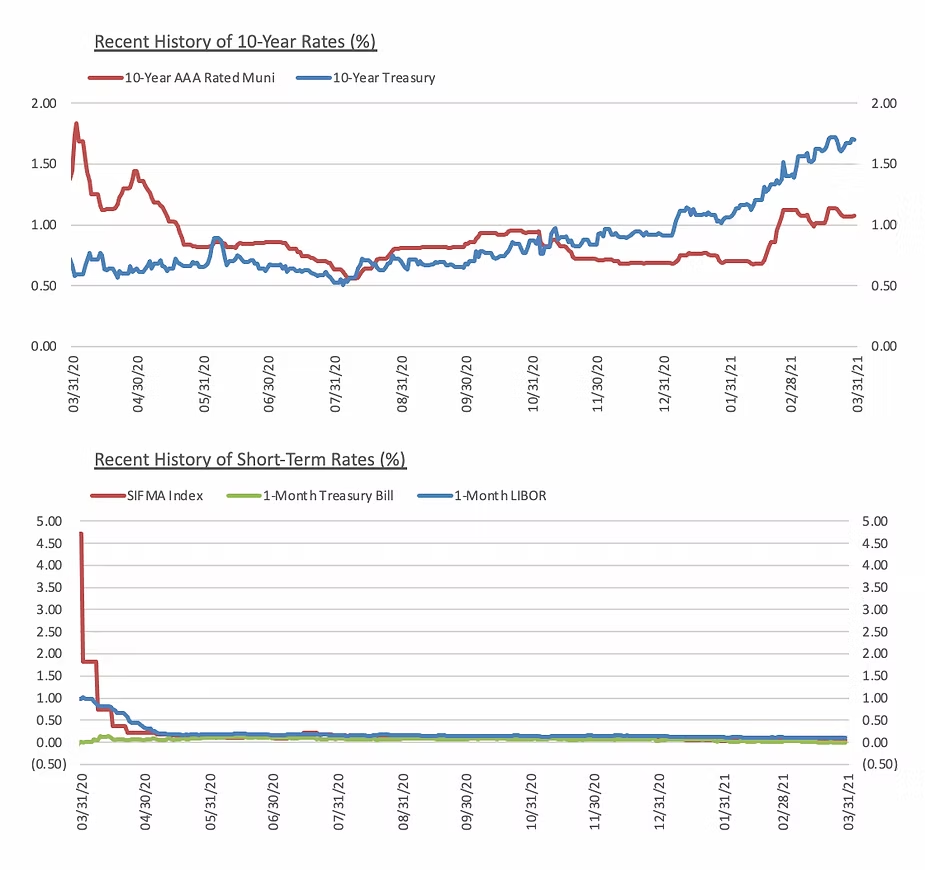

Interest Rates

Talk to a Blue Rose advisor today!

952-746-6050 / [email protected]