In recent months, the growing flatness of the yield curve has been a consistently discussed topic in the market. Essentially, while the “normal” shape of the yield curve has historically been positively/upward sloping (with short-term rates lower than long-term rates), the magnitude of this slope has been shrinking significantly. At present, the difference between short- and long-term interest rates is very minimal when compared to historical levels.

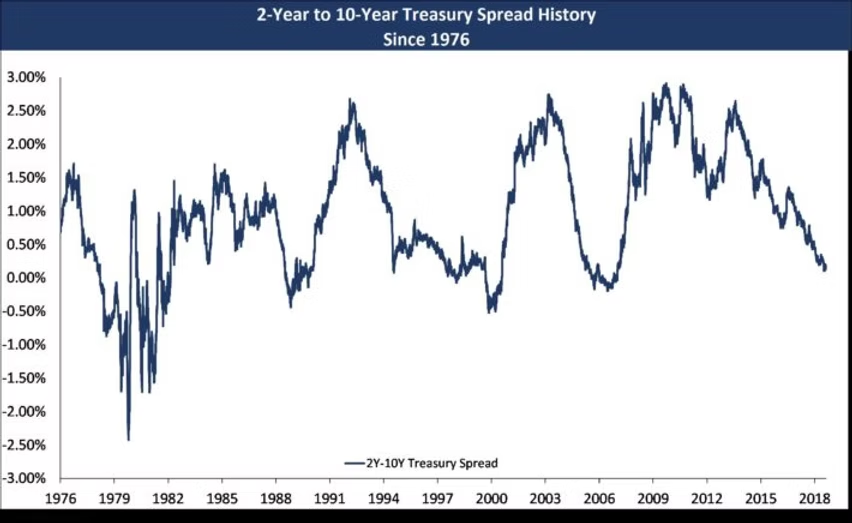

A common market indicator to gauge the shape of the yield curve is the “spread,” or difference, between the ten-year and two-year U.S. Treasury Notes. On December 19, 2018, this spread reached a ten-year low of 10.9 basis points (0.109%), and remains below 20 bps as January comes to a close. In comparison, the ten-year high was 291 basis points (2.91%) on February 22, 2010. While this may seem like uncharted territory given recent market conditions, the yield curve has in fact been flat and/or inverted (with short-term rates higher than long-term rates) on a number of occasions in the past. The graph below shows a long-term history of the difference between the ten-year and two-year U.S. Treasury Notes.

As a result of the current, flatter shape of the yield curve, there are a few key points of consideration that issuers and market participants should be aware of. Firstly, the cost of capital for utilizing a long-term financing structure versus that of a shorter-term financing is compressed relative to the historical norm. Additionally, given that advance refundings of tax-exempt debt are no longer possible due to tax reform, borrowers have been assessing the value and viability of tax-exempt forward current refundings, with a number of these transactions already priced in 2018. Due to the current flatness of the yield curve, the economic cost of executing a forward current refunding has decreased, making these types of financings relatively more attractive than they have been in the past. Similar to forward current refundings, forward-starting interest rate swaps can be executed to lock in refunding savings as well. Furthermore, because the front end of the swap curve is currently inverted, a forward-starting interest rate swap may be less costly than a spot-starting one depending on the term of the forward start. In other words, executing a swap that starts today may be more expensive than executing a swap that starts in the future. That being said, although these reduced costs may appear attractive, borrowers should be judicious in evaluating all economic and non-economic risks associated with the utilization of longer-term debt, forward current refundings, and forward-starting interest rate swaps before making a final decision to pursue such transactions. These options should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Finally, borrowers may find themselves being approached by counterparties regarding the execution of a constant maturity swap (CMS), or may themselves be interested in such a product. Similar to a plain vanilla, fixed-to-floating interest rate swap where one party pays a fixed rate and the other party pays a short-term variable rate (typically based on 1- or 3-month LIBOR), a CMS pays a longer-term variable rate such as the 5-year swap rate. A CMS can also involve the payments based on two variable rates, one short-term and one long-term (also known as a basis swap). Given the flatness of the swap curve, the cost differential between a swap paying a short-term variable rate versus a longer-term variable rate has decreased relative to historical levels and may be attractive to issuers. By utilizing a CMS issued under current market conditions, a borrower with debt based on a short-term index (such as 1-month LIBOR) may be able to effectively hedge its short-term variable interest rate risk with a longer-term variable interest rate. In theory, the borrower in this example will benefit from the receipt of a longer-term rate if the yield curve reverts to a more positive slope, which has been more common historically. However, if the yield curve does not steepen and instead flattens more or inverts, the borrower would be exposed and negatively impacted, as they would be paying more on their debt than they would receive on the swap. Also, since CMS swaps are less common and more complex than more vanilla interest rate swaps, the risk of valuation discrepancies is higher, which could significantly impact collateral posting and market terminations.

As with other market phenomena, the current flat shape of the yield curve presents the market with unique opportunities and products that become more viable and attractive as a result of the changing market conditions. We encourage you to reach out to a Blue Rose advisor to assist in evaluating these concepts and determining whether they may be beneficial for your institution to consider.

About the Author:

Scott Talcott, Vice President

Scott joined Blue Rose in 2016. Scott provides financial advisory services to the firm’s clients with respect to the planning and execution of all types of debt, derivative, reinvestment, and P3 transactions. Scott can be reached by phone at: 952-746-6042 or by email at: [email protected]